Cold Beans Out of a Can

A lawnmower, a broom, a rag, a wrench, a backpack.

This list of everyday items may seem like a simple collection of things lying around the house. But to Harvey Smith, these items illustrate an extraordinary journey of personal and professional achievement that starts one stride behind a lawn mower in an airfield and ends with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin safely setting foot on the surface of the moon.

Harvey Smith’s book “Cold Beans Out of a Can” is available now from Amazon.

In his book, Harvey discloses how aviation was a big part of his life at an early age. Below is an Aeronca 7AC Champion single-engine airplane like the one he soloed at the age of 16.

Time at Tech

“When I got to Indiana Tech in 1959, I took a student-worker position under Professor Bennet Kemp working in the wind tunnel on Saturdays and after school. I worked doing welding and model prep in the aeronautics lab and then started also working on various mechanical tasks in the mechanical engineering lab for Dr. Ivan Planck and professor Edmund Napier.”

Like so many graduates, he relishes what that experience was and the small groups that were created.

“My professors were good leaders over and above,” Harvey said. “Even back then, we had small class sizes which were the best for learning. We were hands-on and really built relationships with our professors. We could do anything. I finished my time designing a high-performance single-seat aircraft for my senior project with instructor Siegfried Brunnenkant. Siegfried was an enthusiastic instructor and Tech grad who had designed a flying wing for his senior project, a very advanced and complicated design at the time.”

Harvey never let the school’s small size faze him.

“It doesn’t matter where you come from, it matters whether you can do the job or not. There should be no intimidators about where students go or where they come from,” Harvey said. “I worked my butt off on all things I have always done. And that is what got me places.”

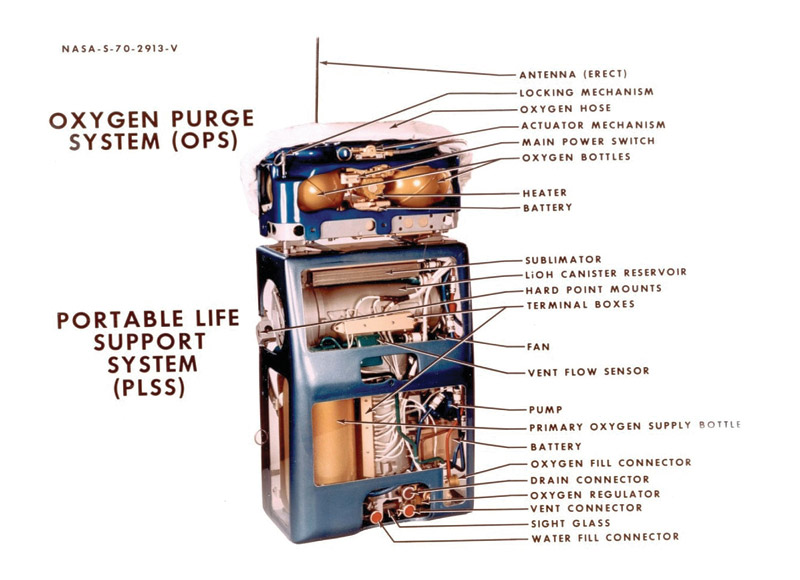

Shown in this NASA/Hamilton Standard diagram is the Apollo 9 Portable Life Support System (PLSS), which was created to keep an astronaut cool, relatively comfortable and—most importantly—alive, in the vacuum of space while allowing them to be independent of the spacecraft’s life support system. The success of this backpack depended on rigorous simulations in various conditions, such as exposure to extreme heat and cold, impacts and vibrations, and zero-gravity environments. Ultimately, the success of the PLSS was a critical part of the Apollo Space Program.

Career after Tech

He used his degree in Aeronautical Engineering to work on projects for the United States Air Force, the United States Navy, the FAA and Naval Air Turbine Test Station. He then moved on to a position with Hamilton Standard’s Division of UAC in Connecticut as they acquired a contract with NASA’s Apollo Space Program.

Armed with a slide rule, a wealth of engineering experience and an unwavering confidence, he was approached by the head of Space System Mechanical Design to take over the Apollo Backpack Design effort which was in trouble. From there, Harvey took the helm of more than 50 engineers from all across the country to finish the design of the Portable Life Support System that would keep a human being cool, relatively comfortable and ultimately alive in the vacuum of space.

In the book, Harvey included a photograph of his slide rule that was used by him and all space program engineers and reflected, “Someday, people will laugh when they look at the tools we used to get there. But that was real for us. It is what we had to get a man onto the moon safely. We had to develop so many things from scratch, completely new to the world, even conceptually.”

Looking back, Harvey credits all of those who helped him along the way: the pilots at the airfield who inspired him, his teachers and Indiana Tech professors who guided him, the supervisors who tested him and the astronauts who trusted him. From the earliest stages of his education, to the very culmination of his life’s work, Harvey beams knowing that, “there are a lot of good people out there that were willing to help. Most of those who helped me didn’t let me know until I was an adult.”

Harvey’s moment of truth came when astronaut Rusty Schweickart stepped out into space for the first time wearing the life support system that the Hamilton Team designed. Everything before that spacewalk was simulated in a controlled laboratory environment where he and his team knew everything that could be factored.

“There was always a thought in the back of our minds of ‘did we get it all?’ And we did. Those astronauts are a different breed, they strap in knowing very well they are being put in harm’s way and they go anyway. I feel honored that I was able to work on it in my lifetime.”

Beyond the Book

The heart of Harvey’s story is a lesson in the benefits of a sound work ethic and the payoff that comes from believing in the possibilities within oneself.

“Even when I had nothing, even when I was eating cold beans out of a can, I never thought of quitting,” Harvey said. “You might make mistakes, but if you never try, you’ll never get there.”

Always curious, Harvey ponders what our next great achievement will be.

“We have to wonder, what’s coming next? Interplanetary travel? The future is interesting; humans are always thinking. Same barrier as getting to the moon, there are goals and there are ways to get there. We just have to figure out how to answer the question of ‘how can I solve this problem?’ I remember when we first broke the sound barrier and how exciting that was. It’s human nature to explore, to push beyond and to figure things out. We will keep going.”